WHEN HAILWOOD DROVE FOR SURTEES

Mike Hailwood took easily to Formula 1. Its driving aspect, at least. At the second attempt, that is. His first had been premature and beset by distraction and frustration. A god on two wheels one week, he’d be lumbered with a four-wheeled dog the next. He railed against its claustrophobic cockpits and cloistered paddocks, too.

Perhaps lulled by John Surtees’s seamless bike/car transition of 1960, Hailwood had underestimated the task. He had made his Formula 1 debut in the 1963 British Grand Prix at Silverstone after just three Junior single-seater races – two of which he’d won. He finished a distant eighth in a privateer Lotus, and contesting all bar one of the Formula 1 Grand Prix in 1964, he scored just one point.

Hailwood was born to race motorbikes. Winning every other weekend on MV Agusta’s peerless 500cc, now he was dying on his arse in cars. What’s more, he was paying for the ‘privilege’ via an unwise investment in the late Reg Parnell’s team; Mike had inherited none of his millionaire father Stan’s acumen. Eventually, after a disappointing 1965 Monaco GP, he sold back his share and returned to the two-wheel paddock.

One of the true motorcycling greats, Hailwood put his legacy on the line by pursuing a career on four wheels.

DISASTER

“For me, F1 was an opportunity,” says Richard Attwood, Hailwood’s team-mate at that Monaco race. “But for Mike, it was a disaster. He was probably too busy to test properly and perhaps didn’t give it a fair go. When I’d gone to the team’s Hounslow base to see if I fitted the car, I noticed that its steering wheel was labelled ‘steering wheel’. And there was a note saying ‘gear lever’ with a big arrow pointing to the gear lever. Mike! Taking the Mickey straight away.

“He was very flippant, in a defensive way. But I concentrated on my own thing and so was only vaguely aware that he was struggling. After qualifying he realised that I had more ability than he’d given me credit for and we ended up having the most fantastic weekend. We saw the dawn come up and were blood brothers by the end. He proved much later how quick he could be in a car. Stunning on occasions. I think he might have been faster than Surtees, certainly on a par.”

Hailwood returned to F1 six years – and five more two-wheeled world titles – later, driving for Team Surtees and scratching for victory in a frantic Italian GP that would go down in history: five men desperately seeking their maiden victory were separated by six-tenths at the chequered flag. Though 31 already, Hailwood had just joined Ronnie Peterson (second) and François Cevert (third) in the ‘new generation’.

With the help of another TT legend, Hailwood would work his way back to the front row.

SURTEES & HAILWOOD

There was inevitability to Surtees & Hailwood. Their fathers had raced each other, and Mike had followed John from Norton to Parnell via MV. But whereas Surtees was intense, studious and technically minded, Hailwood’s idea of a successful debrief was a racy conclusion to another wild night.

“Mike was a natural rider,” Surtees said of him. “But when he came to cars, he wasn’t getting the best out of himself relative to their set-up. He had no knowledge yet wouldn’t ask for help. It was me who had to approach him: ‘You need to drive for another motorcyclist who understands what you’re feeling.’”

The resultant relationship was forged in Formula 5000 during the bulk of 1971, Hailwood having already enjoyed two convivial and competitive seasons in these rugged single-seaters, winning twice in twitchy Lolas. In fact, he’d never really left cars.

Honda’s surprise withdrawal from motorcycling after 1967 – it paid Hailwood a £50,000 retainer not to ride for anyone else – had left him at loose end. Now he could concentrate on racing cars and, determined to learn the craft, he would do so out of the F1 spotlight and at a pace that better suited his diverse career.

The one that got away? Hailwood came close to winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans during the event’s golden age.

LE MANS

“He was just brilliant,” says legendary British racer David Hobbs. He danced unbelievably well. Played clarinet, guitar, drums and piano. A fantastic water-skier. Had a girl in every port. He was quite remarkable so I was full of enthusiasm when he became my co-driver in a Gulf GT40 for 1969.

“We would have won at Le Mans but for Yorke. We were a lap ahead when our brake pedal went to the floor. Yorke immediately ordered a pad-change. I shouted, ‘No, it’s more than that!’ He ignored me. Sure enough, I almost ran over the poor marshal at the end of the pit lane and we lost more time with another stop after a slow lap. A balance weight had chafed through the caliper’s bridge pipe.”

Hailwood/Hobbs eventually finished third behind the victorious Ickx/Oliver. Reunited at Le Mans the following year, this time in a Gulf Porsche 917, Hailwood would suffer his most embarrassing accident.

“He came in for a scheduled fuel stop [from third place after three hours] and it started spotting with rain,” said John Horsman, the team’s chief engineer. “Asked if he wanted intermediates fitted, Mike declined. The heavens opened two or three minutes later. We had the jacks and tyres ready, but he went sailing past.”

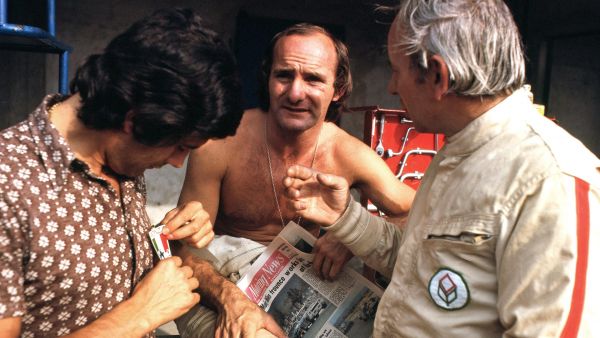

A meeting of minds: TT legends Hailwood, Agostini and Surtees catch up at Monza in 1972.

UPWARDS

‘Micycle the Bicycle’ had yet to convince the four-wheeled fraternity: Motor Sport correspondent Denis Jenkinson, a former sidecar world champion, was snippy about his larrikin image; and others queried his continuing to compete on bikes occasionally.

“Being in and out, he had made few friends in cars,” said Surtees. “And he used to get terribly wound up before a race, so there wasn't much point sending him to bed early. He'd never have slept anyway. But I had an extremely high regard for him and a lot of confidence in him. The others had to take him seriously when he started doing it properly.”

Indeed, Surtees’ confidence in Hailwood was looking well placed in 1972, despite a number of retirements. Still, the motorcycling legend finished fourth in the Belgian GP, sixth in the French GP and fourth in the Austrian GP. He also qualified on the front row for the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch. Then there was another starring role at Monza: had his airbox not come adrift, costing him 300rpm, he might have won the Italian GP rather than finish second behind world champion Fittipaldi.

A concurrent Formula 2 campaign with Surtees brought him even more success: second place and a (forever) lap record at Crystal Palace; second and fastest lap at Rouen; second at the Österreichring; a heat win at Sicily’s Enna-Pergusa; and outright wins at Sweden’s Mantorp Park and Austria’s Salzburgring. He would secure the European Championship at Hockenheim with another measured second place.

Mike Hailwood and his Surtees negotiating the famous Karussell corner at the Nürburgring.

DOWNWARDS

In contrast, his 1973 began to unravel from the moment in March – just five laps from victory in the Race of Champions – when the rear suspension collapsed again. Hailwood threw his helmet to the ground in a rare display of petulance. Those F1 frustrations were building again.

“We were the first to build a full crushable crash structure for the new regulations, and that worked against us when the governing body backtracked; our car could have been lighter,” said Surtees. “Then Firestone withdrew. They backtracked, too – but made just one type of construction. It didn’t suit us and our fronts were destroyed. We did an awful lot on not a vast budget – but there were lots of silly things. It was a shame for the both of us.”

Hailwood was ripe for change. Normally he had no time for F1’s financial shenanigans, but when Surtees was obliged to accommodate a new sponsor’s insistence upon a certain driver, and McLaren was hectored into running a third car to appease an established sponsor refusing to be jilted, he grabbed the resultant opportunity for 1974 as though it were his last.

In Vogue: Hailwood finally relaxed into the F1 paddock, but his best days wouldn’t last long.

PROMISE

Hailwood was finally in an F1 car that went where he pointed it. Slick tyres and wings also suited his bike-bred neat style and fast-corner commitment. He finished fourth in Argentina, fifth in Brazil and third in South Africa: the only driver to score in each of that season’s first three GPs.

“He was delighted with the results and felt he was achieving something,” said his wife, Pauline Hailwood. “I think he could have won a GP. I think he thought so, too. He was full of confidence now.”

Unfortunately, while battling Lotus duo Peterson and Ickx for fourth place at the German GP, Hailwood landed awkwardly from one of the old Nürburgring’s many jumps and turned sharply right into a barrier.

“He broke both legs,” said Pauline. “The left was quite straightforward. The right was complicated: the heel was shattered and the ankle pushed down and compacted. It soon became clear that the doctors couldn’t fix it. Mike was devastated.

"He had quite a few operations and lots of rehabilitation. The spirit was willing but the body wasn’t up to it. There were plenty of sad moments and it took him a long time to readjust. He suffered withdrawal symptoms. I don’t think he’d ever looked on F1 as a bit of a lark.”

No, but Hailwood’s relationship with racing cars had been testy from the moment he crashed an F1 Lotus during an exploratory test at a wet Silverstone in 1961. “He always felt that he was a biker,” says Attwood. “We were holidaying somewhere when Hobbs said, ‘Why don’t you put your leathers on?’”